During the Ottoman period, Jewish communities in the principalities of Moldova and Walachia enjoyed judicialand fiscal autonomy, and the organization of religious life was similar to that in the Ottoman Empire. The communities were headed by the 'Hacham Başı' (the Chief Rabbi) and his seat was in Iași. In addition, the communities were also part of the secular Jewish "breasla jidovilor" - the official institution of the Jewish community, which was one of 33 guilds representing national minorities, such as Armenians, Greek sand various trade unions. The main task of the guild was to supervise the payment of collective tax to the Jews, part of which was devoted to the financing the Jewish community institutions.

At the head of each guild was the 'Starosta', elected by members of the community for a limited term, which required the approval of the Prince. As Jewish communities grew, the number of community leaders rose to three, one of whom was the head. The role of the 'Starosta', whose position was originally defined at the beginning of the 18th century, began to lose power by the end of that century as a result of demographic and economic changes that affected the Jewish society.

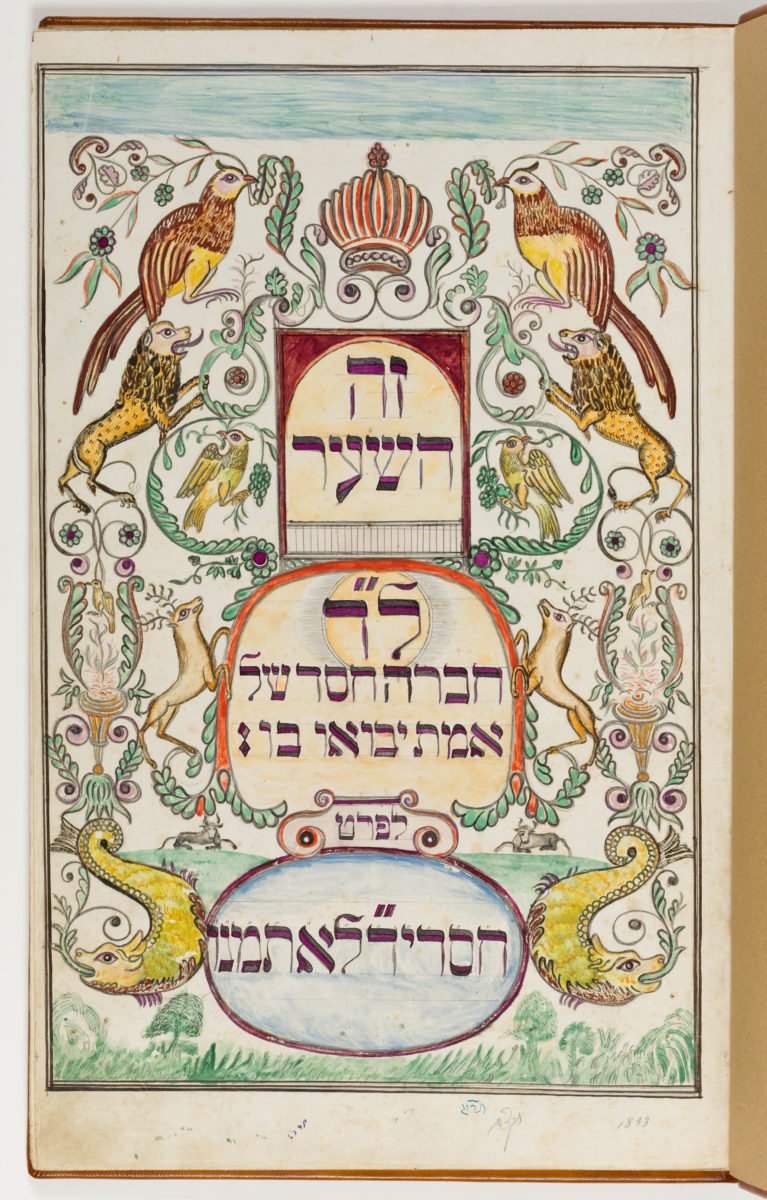

At the same time, the religious leader, 'Hacham Başı', head of the autonomous judicial system of the Jewish communities, became more and more responsible for secular matters, such as tax collection and its transfer to the central government. The community's rabbis recorded births, marriages, and deaths, and were also authorized to hear civil trials. Their decisions could be appealed to the 'Hacham Başı'.

At the beginning of the 19th century, following the great wave of Jewish immigration from Galicia, Poland and Ukraine, many Jews with leanings toward Hasidism arrived to Moldova, and by the second half of the 19th century they numbered 85,000. Those immigrants, who held foreign citizenship, differed in their customs from the local Jews, and were organized in separate communities. They refused to accept the Hacham Başı's authority and offered to pay taxes directly to the state. Against this backdrop, disputes arose between them and the local communities.

Alongside Ashkenazi and Hasidic communities, there were communities of Sephardic Jews in Romania who came toWallachia from Bulgaria, Serbia, andTurkey. In 1730, the ruler of Wallachia, Nicolae Mavrocordat, gave his Jewish advisers, Doctor Daniel de Fonseca and Mentes Bally, power to establish a Sephardic Jewish community. But it was only in 1830 that a separate Sephardic community was established in Bucharest. At the beginning of the 20th century, the number of Sephardic Jews in Romania reached about 12,000. They were concentrated in Bucharest, Craiova, Turnu Severin and Constanța, and for many years maintained their traditions and kept separate synagogues, educational systems and aid organizations.

The Organic law (Regulamentul Organic) of 1831 and 1832 and other laws that followed, harmed the Jews, turning them from native citizens into "foreigners", and the Jewish community was no longer recognized as a guild but as a separate "Jewish nation". In 1834, the position of the Hacham Başı was abolished and then replaced by a ten-member council called ”Epitropie”. After the government abolished the recognition of the Old Kingdom (Regat) Jewish communities in 1866, Jews were not represented under any independent legal body until 1928 when the first religious law in Romania was passed.

With the cancellation of the Hacham Başı's role, the community's framework was also undermined. In Moldova andWallachia these events took place against the background of internal conflicts already existing within the communities. The conflicting sides complained to the authorities, and the various organizations fought against one another. The Sephardic communities, which maintained internal organization and served as examples of good governance, were outstanding. Only in Ploiești, there was a joint community of Ashkenazim and Sephardim that functioned properly and continuously.

After 1918, the main challenge faced by the Jews of Romania was the organization of community life and religious life, despite their unclear legal status and the differences between the communities. As far as the internal organization is concerned, the years after World War I were fertile years. Throughout the country communities were reorganized, membership boards were democratically elected, and representatives of all sectsand social strataparticipated. In 1923 the "Union of Native Jews" established in the Old Kingdom, became the "Union of Romanian Jews" with Wilhelm Filderman as chair, and Rabbi Dr. Jacob Niemirower was elected the first Chief Rabbi since the cancellation of the 'Hacham Başı' in 1834.

Only in 1928 did the Romanian government approve religious law and Jews became recognized as a religious minority. Once the law was passed, Jewish public opinion was divided over whether Jews should establish their own national party, which would represent them, or if they should participate as part of the general population. The "Union of Romanian Jews" opposed the establishment of a Jewish party and triedunsuccessfullytoinfluencevariouspartiesto adopt a pro-Jewish political attitude as a condition for recommendingthatJewsvote in their favor. On theother hand, there were young leaders who supported the establishment of a Jewish party, and in theelections of 1928, four representatives of this party were elected to Parliament from Transylvania, and from Bessarabia. In 1930, a Jewish party was formed in the Regat, and in the June 1931 elections, the Jewish party won 5 parliamentary seats.

In 1933, the Union of Romanian Jews was disappointed with the prospect of cooperation with the general parties, and it established the Joint Jewish Front with the Jewish National Party, which tried unsuccessfully to combat anti-Jewish policies. However, until the enactment of anti-Semitic laws at the end of the 1930's, Jewish communities enjoyed autonomy and maintained religious, educational, health and welfare services, funded by member'staxes. The Jews of Romania maintained a communal framework that took care of the needs of its members and represented them to local authorities untilthe anti-Jewish laws paralyzed its activities.

Duringm the Communist era, the community's institutions continued their activities to the extent that the government allowed. In 1960 there were 153 Jewish communities in Romania with 841 synagogues, 67 ritual baths, 86 kosher slaughter housesand a matzoh factory. In Iași andBucharest there were several Yiddish schools and 54 Talmud Torahs. All of these continued operating until the mass emigration in 1964. Today Romania has a small Jewish community of about three thousand people, mostly elderly.