The treaties that followed World War I more than doubled the territory and population of Romania. According to national census of 1930, there were 756,930 Jews, about 4.2 percent of the total population. The new borders of Greater Romania added three distinct Jewish communities: 206,958 Jews in Bessarabia, 92,988 in Bucovina, and 193,000 in Transylvania. At that time there were 263,192 Jews in the Regat. Most Jews (about 68 percent) lived in urban areas, and in large cities: in Iaşi 35,465 (34,5 percent of the town's population), in Galați, 19,915 (19,8 percent) and in Botoşani 11,840 (36 percent). However, the highest Jewish urban concentrations were in Bucharest, 76,480 (12 percent), Cernăuţi, 42,932 (38,2 percent) and Chşinău, 41,405(36 percent).

Each of these groups was a historic entity, with its own unique character. The Jews of Bucovina, Transylvania, and Bessarabia were radically different from those in the Regat in terms of Jewish identity, internal organization, civil status, and economic importance. The Jews in the Regat were, to a greater extent, acquainted with Romanian language and culture. The Jews of Bessarabia formed the most traditional group. Yiddish was its spoken language and Hebrew its culture, though there were also signs of the influence of the Russian culture and modern political ideas. The Jews of Bucovina had developed an elite affiliated to German culture.

The situation in the district of Ardeal, which included both Transylvania the Banat, was more complicated. Jewish society in Transylvania was divided between an Orthodox community and a Neolog one, as in Hungary before World War I. In the northern Crişana and Maramureş regions, traditional communities were maintained. They spoke Yiddish and belonged to an extreme branch of religious orthodoxy. The rest of Transylvania and the region of Banat, had Neolog communities in the large cities, and were totally assimilated into Hungarian culture in terms of language and identity. When Transylvania become part of Romania, the process of "Magyarization" slowed in favor of a strengthening Jewish identity.

Tradition and the different cultural influences created a barrier to the development of relations between the Jews of the Regat and the three new districts. The twenty years between the world wars were not sufficient time for the fusion of these four groups into a single unit. On the one hand, the Jews of the Regat felt superior to the Jews from the new districts, due to their familiarity with the Romanian culture. On the other hand, the Jews from the new districts felt that they were superior: those from Bessarabia because if their Hebrew culture, and those of Bucovina due to their experience in political life and their western culture. The Jews of Transylvania had more political experience, but the process of "Magyarization" they had undergone created a barrier to any mutual influence between them and the Jews of the Regat.

The new Romanian state was multinational, and the government tried to enforce a policy of "Romanization". However, almost every segment of Romania's Jewish population was viewed with antagonism by the Romanian elites of the new state. The Jews of the Regat, assimilated in Wallachia, but less so in Moldova, were viewed with antagonism for all the reasons that had fostered the growth of Romanian anti-Semitism in the decades before World War I, political, economic, cultural and religious. Furthermore, foreign support for their struggle to obtain citizenship had led to a widespread sentiment that the Jews, with the help of outside powers, were seeking to limit the sovereignty of the Romanian state.

The Jews of Transylvania and Crişana and Maramureş, the majority of whom spoke either Hungarian or Yiddish, were viewed as "foreign", both because of their religion, and because their cultural identity and political loyalty had been shaped with the Magyar majority in Hungary. The Jews of Bucovina, culturally aligned with the Germans in the Habsburg monarchy, or speaking Yiddish were also considered "foreigners" by the Romanians, since they had lived in a region of historical Moldova, seized by the Habsburgs in 1775, and returned to Romania only in 1918. The Jews of Bessarabia, mostly Yiddish and Russian speaking, who lived mainly in the countryside, served as the model of the stereotypical foreign Jew against which anti-Semites in the Regat had been agitating for decades.

In this atmosphere it is not surprising that anti-Semitism was a common phenomenon in Romania after World War I, and manifested itself in three forms, political, cultural and popular. Thus, the Jews suffered both from the minorities who wanted to preserve their unique character and regarded Jews with suspicion, and from the central government which wanted to suppress all minorities, including the Jews.

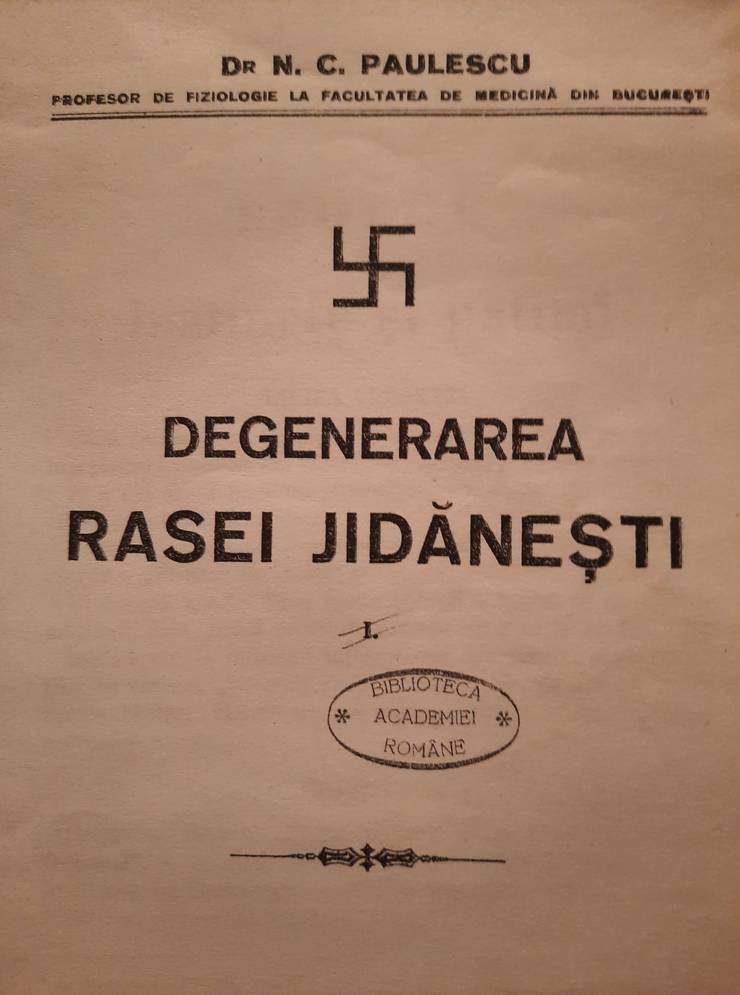

From the earliest decades of the development of modern Romania, there was a strong anti-Semitic current in the country's political and intellectual life that was not on the fringes of the society, but at its very heart. Moreover, the language used to discuss the denial of citizenship, physical expulsion, ritual murder accusations, throwing into the Danube, attack on Jewish religious belief and practice, designation of Jews as foreign agents, enemies of the state and the nation, the language of separation, dehumanization and killing appeared early on the Romanian scene. In fact the extreme anti-Semitic language introduced in those years echoed through the following decades, during and even after the Holocaust.

In 1922, the students at the University of Cluj, declared a numerus clausus (quota) against the Jews, and used violence to enforce the restrictions. The students of other universities followed their example, and in 1927, the Romanian nationalists united to form a political movement, the Iron Guard. This organization adopted an extreme anti-Semitic policy alongside its line of violence and terror.

The policy of discrimination against the Jews in different professional fields and especially in the civil service continued. Yet, in other areas there was an improvement in the atmosphere of antagonism towards the Jews. The educated circles were the first to show more tolerance. The works of Jewish authors were published in periodicals, and Jewish writers played a part in the flowering of Romanian literature. Jews played a prominent role in the fields of Romanian literature, music, theater and painting, and only the universities were closed to Jewish scholars, due to the terrorist activity of the students.

Paul Cenovodeanu, Liviu Rotman, and Raphael Vago, eds. Toldot ha-yehudim be- Roamnyah, Vols. 1-4, Tel Aviv, 1996-2003

Carol Iancu, Les juifs en Roumanie, 1919-1938, Paris, 1936

Ezra Mendelsohn, The Jews of East Central Europe between the World Wars, Bloomington, Ind.,1983