In the early decades of the 20th century, several young avant-garde artists from Romania, most of them Jewish, conquered the art world by storm. Five of the artists who were actively involved in the birth of the Dada movement in Zurich were Jews born in Romania. Art scholars have tried to establish their sources of inspiration. Some claimed that they found inspiration in the Hasidic culture

which in the early 20th century was still prevalent in some shtetls in Moldova. But this theory is difficult to prove, since the artists themselves were not religious, and did not come from religious or Hasidic families.

The explanation for the large number of Jewish artists in avant-garde circles may be rooted in the complex and problematic relationship with the Romanian culture and the particular affinity of Jews to revolutionary modernism. The Jews, more than any other "foreigner" were, in the eyes of Romanian nationalists, an enemy from within, and a threat to the unity of the nation. They believed that Jews differed not only in their religion and culture but also racially, calling them not only "Străini" ("foreigners"), but "venetici", a pejorative term meaning, “foreigners who invade a place that is not theirs".

The Anti-Semitic university professor Alexandru Cuza applied these notions to artistic creations. In his book "Naţionalitatea in arta" ( Nationality in Art) published in 1908, Cuza defined a nation as a being of a homogeneous ethnic entity and argued that art, the supreme expression of culture, must be intrinsically related to nationality, therefore foreigners cannot express the true nature of Romanian culture. The foreigners that Cuza is referring to were first and foremost Jews, who, in his opinion, were "definitely an inferior ethnic group" of a different race, culture, and incapable of assimilation. For Cuza, the idea that "beauty has no homeland" was heresy.

Tristan Tzara was born in Romania in 1896, but like most Romanian Jews at the time, he was not a Romanian citizen. His birth certificate stated: "Samuel (Shmuel) Rosenstock, a son of parents belonging to the religion of Moshe, a Jew, is not entitled to any protection." Also, M. H. Maxy's birth certificate from 1895, mentioned that he was the son of a "foreign carpenter belonging to the Jewish nation."

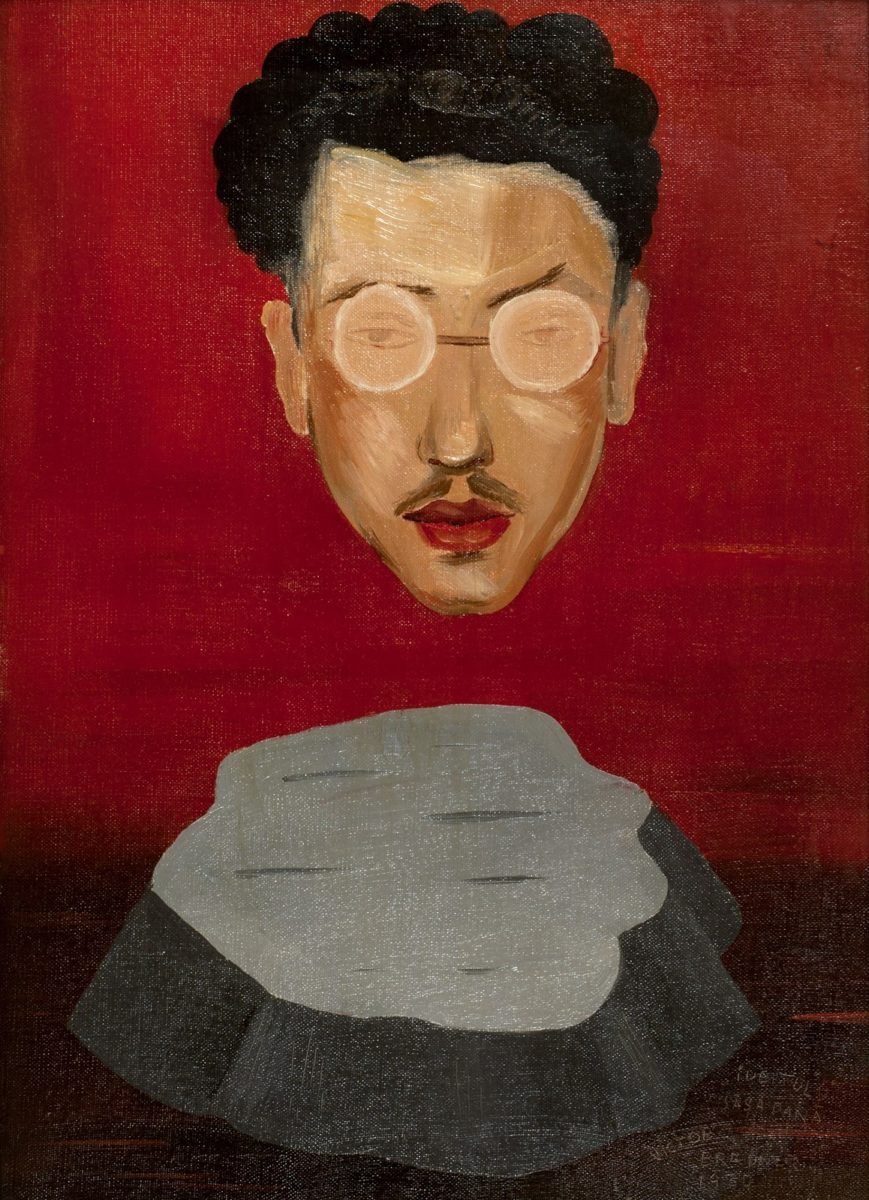

Most Romanian intellectuals at the time adopted Cuza's notion that only Romanians by blood could be true Romanian artists. Therefore, it is no wonder that criticism of the works of art created by the Jewish avant-garde artists was not directed at the work itself, but to their ethnic roots. For example, writings about Victor Brauner's first exhibition in 1924 stated that it was a product of a "dark foreignness" and subversive actions which needed to be reported to the secret police. The sculptor Horia Igirosano, who was the art critic of the conservative magazine "Clipa" (Moment), called Marcel Iancu (Janco) and Max Hermann Maxy not only "crazy" but "foreigners in our country."

Obviously, under these circumstances, it was difficult for Jewish artists to identify with the culture which rejected them, and the universality and cosmopolitanism of the avant-garde was a clear source of attraction for them. Thus, among the avant-garde artists in Romania, the Jews constituted the majority, and the most prominent among them were Tristan Tzara, Marcel Iancu, Arthur Segal, Max Hermann Maxy, and Victor Brauner. They looked for an art of a different kind in which their "otherness" created no obstacles. Their words, "We strongly reject the false tradition of the soil and bow to the endless tradition of man. The first is conservatism, the second is civilization", were published in an editorial in the avant-garde journal "Integral" subtitled "The Journal of Modern Synthesis" published from 1925-1928 and edited by Max Hermann Maxy.

In this sense, the Judaism of the artists, an obstacle in "national art" paved their way towards revolutionary modernism. In other words, the fact that most of the avant-garde artists from Romania were Jewish indicates that the problem was rooted in Romanian culture of the period and not in Jewish culture. Thus the attraction of some of the Jewish artists to revolutionary modernism seems an obvious choice.

During the 1920's, a wave of artistic innovation began in Romania as Jewish artists connected with artistic movements protesting against a society that did not grant Jews civil rights. Marcel Iancu, who returned from Zurich to Bucharest in 1921, Max Hermann Maxy who returned from Berlin in 1923 and Victor Brauner worked together to revamp the art scene.

The avant-garde periodical "Contimporanul" (Contemporary) edited by Ion Vinea and Marcel Iancu was first published in 1922. In late 1924, Janco and Maxy organized the International Exhibition of the Bucharest periodical, which became one of the largest avant-garde exhibitions at that time. In October 1924, HP75 magazine was published by Victor Brauner and Ilaria Voronca (Eduard Marcus). Literary critic Eugen Lovinescu defined the only published issue as "a pure Jewish enterprise" and "the most avant-garde experimental publication in Romania."

The second wave of avant-garde artists in Romania centered on "unu" ("one"), a magazine published by Sașa Pană (Alexandru Binder). Victor Brauner published his drawings in the fourth issue of the journal, and continued to contribute to the journal regularly until he left for Paris in May 1930. Jules Perahim (Blumenfeld) showed his works for the first time in "unu" and then went on to contribute to the journal drawings and prints.

The late 1930's were very difficult years for Romanian Jews, and artists, like other Jews, suffered from ethnic attacks. In a cartoon published in the fascist Romanian newspaper "Porunca vremii" (Order of the Hour), Max Hermann Maxy is described as the "Jew Maxi Goldenmayer-Stern", possessing a large nose, painting with ”kosher ink and "poisoning the art with the venomous snake which he uses as a brush”. Victor Brauner, concerned about the situation in Romania, reduced the size of his paintings to "suitcase paintings" as he called them, so he could place them inside of a suitcase in times of emergency. In 1938 he moved to Paris and never returned to Romania. Janco, who was equally troubled by anti-Semitism in Romania, traveled to Palestine for the first time in 1938, and in early February 1941 he left Romania again and traveled to Israel. Jules Perahim fled to the Soviet Union and returned to Bucharest only in 1944. Until he left for France in 1969, Perahim had abandoned the art of the avant-garde in favor of socialist realism and returned to surrealism only upon his return to Paris. Paul Păun, who had been forced to cease all artistic activity during World War II, opened his first solo exhibition in 1945 and participated in a group exhibition of surrealistic artists in Bucharest in 1946. The following year, the works of Păun and the surrealists were censored. With the establishment of the People's Republic of Romania, the art of avant-garde in Romania had come to an end. Paul Păun, who had to work underground, left Romania and immigrated to Israel in 1961.